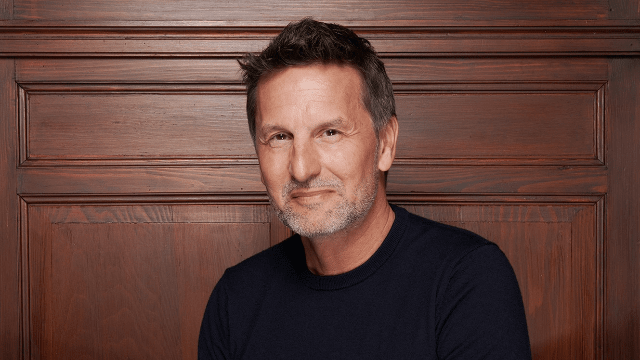

Maximilian Büsser, a microengineering graduate from EPFL, is the founder of MB&F – one of the world’s most innovative watchmakers. Its 3D timepieces are inspired amongst others by popular culture and have won nine Grand Prix d'Horlogerie de Genève awards. We spoke with Büsser about his career, how he’s upended tradition in his industry and the future of his company.

Where did you grow up, and why did you decide to attend EPFL?

I was born in Italy to a Swiss father and Indian mother. My family moved to Switzerland in 1971, when I was three years old. I was pretty introverted as a child but had a vivid imagination – I liked to picture myself as Han Solo, Grendizer or an airplane fighter pilot. I also loved to draw cars. My childhood notebooks are full of sketches of them!

I graduated from high school in 1985. That same year, the Pasadena ArtCenter – the world’s most prestigious design school – opened a European branch in La Tour-de-Peilz. I would’ve loved to study there but the tuition was CHF 50,000 per year, which was more than my parents could afford. My father really wanted to help me but the cost was so high that I dropped the idea. Instead, I enrolled at EPFL, like most of my classmates with a knack for science, with the idea of studying design later.

You began working in watchmaking as soon as you graduated from EPFL. How did your initial love of cars evolve into an interest in watches?

I majored in microengineering since I figured that way I could keep my options open. Back then, EPFL was nothing like it is today – it mainly trained engineers for local businesses. In 1988, when I was in my third year, we had to complete a project called Man-Technology-Environment. It was a great experience since it was our first project that included human aspects. I picked high-end mechanical watchmaking with the goal of understanding how a technology that seemed obsolete could be so expensive.

With the naivety of youth, I sent letters to the CEOs of the most famous watchmaking brands: Audemars Piguet, Vacheron Constantin, Jaeger-LeCoultre and more. Switzerland’s watchmaking industry was in serious jeopardy at the time and the companies were very far from their former glory. The CEOs all agreed to speak with me, which would be unthinkable today. They all shared their sadness to see this industry decline since all these artisans, who had passed on their skills through generations, had one goal: to create beauty. That was the first time I heard of an industry that associated engineering with humanity and creativity. And I fell in love…

MB&F Manufacture Workshop

MB&F Manufacture Workshop

From there, how did you turn your newfound passion into a career?

I completed my first internship in 1991, spending six weeks at Audemars Piguet. But I didn’t think I’d actually work in watchmaking since the industry was in serious trouble. Just before graduation I started applying for jobs at large companies like Nestlé and Procter & Gamble.

However, a chance meeting brought me back to watchmaking. One day while I was skiing, I ran into the CEO of Jaeger-LeCoultre, Henry-John Belmont, whom I’d interviewed several years earlier. A week later he asked me to come meet him at the factory and took me on a tour of the company workshops. He then offered me a job as a product manager. When I mentioned the other job interviews I had lined up, he asked: “Would you rather be one of hundreds of thousands employees in a large corporation, or one of the four or five of us who will save Jaeger-LeCoultre?” I called him the next day to accept his offer.

Before founding MB&F, you built your reputation by helping turn around Jaeger-LeCoultre and then Harry Winston’s watchmaking business. What were the keys to your success?

The first years at Jaeger-LeCoultre, I spent the entire working week in the Vallée de Joux and went home to Lausanne for the weekends. Our business days generally ended with us all having dinner together and continuing to talk about our ideas and sketch out new products. I was 24 years old at the time and found the experience extraordinary. Over the following years, the company’s revenue grew from CHF 17 million to CHF 150 million. Here the key was our team: down-to-earth people who were highly motivated, caring and united in a common goal.

In 1998, when I was 31, I was contacted by Harry Winston – one of the world’s most famous jewelers – to head its watchmaking division. Shortly after I signed my contract, I found that the situation was catastrophic: the parent company had been put up for sale and the watchmaking business was about to go bankrupt. Personally, it was the toughest year of my life: an insane amount of stress, crazy working hours which resulted in a massive ulcer. But after eighteen months of misery, we pulled through: our revenue grew thereafter from $8 million in 2000 to $80 million in 2005.

The key to this turnaround was to position the company as a high-end watchmaker rather than placing all our bets on jewellery quartz watches that would have been perceived as accessories. The Opus collection also broke ground because we credited for the first time each watchmaker who had engineered the timepiece.

I started working alone in my apartment. All I had was a sketch of my first watch, the Horological Machine No.1. For me, watchmaking is an art form.

You founded MB&F in 2005 using only your own funds. What prompted you to make such a decision?

At the time, I had every reason to be happy – a prestigious job, a high salary, noteworthy achievements – but I wasn’t. I didn’t feel free: I had become a marketer, creating products based on potential sales, and not on what I loved. Late 2001, my father passed away. That in turn led me into a therapy, which made me realize that the most important day of my life would be my last – and that I better be able to look back and be proud of what I’d accomplished.

Professionally, that meant being free to express my creativity without thinking about sales targets, and work surrounded only by people who share my values. I gradually started obsessing about this crazy dream. Harry Winston offered me a new contract in 2005 with excellent terms but that also contained a non-compete clause and non-solicitation of employees and suppliers clauses. It was a decisive moment for me, because signing the contract would’ve meant giving up on my dream. I left Harry Winston on 15 July 2005 and founded MB&F – which stands for Maximilian Büsser & Friends – ten days later.

You’re known for your futuristic, abstract timepieces. What did your first watch design look like?

I started working alone in my apartment. All I had was a sketch of my first watch, the Horological Machine No.1. For me, watchmaking is an art form. A lot of people feel the same way, yet so many watches look alike. I wanted to create unique 3D kinetic sculptures. My first design was modeled after the human body – a completely original concept – with lungs on each side and a heart in the middle that transmitted information to the watch hands. Thousands of hours of design work went into that watch.

Your approach involves a lot of risk taking. How were you able to stabilize your company financially?

We faced many major challenges between 2005 and 2015. Virtually all artisanal watchmaking firms that launched in those years faced similar problems. We all knew the journey would be incredibly difficult and dangerous but it was the price to pay for our independence.

The 2020 pandemic was a pivotal moment. I didn’t think the company would survive since our retailers and suppliers were all closed, and our customers were locked down at home. But the opposite actually happened. Many people used their free time to learn more about our watches, and thousands of requests came in. Demand very quickly outstripped supply, since we crafted only 280 pieces per year and did not want to grow. My goal was to break creative new ground and innovate, not to grow our company or revenue.

One day, one of our retailers offered to open an MB&F store in Beverly Hills, on Rodeo Drive, but he wanted of course that we increase his allocation. That was also when I started thinking about my succession. Most of our customers were people whom I’d met personally, and I realized that opening retail outlets would be a way to separate our brand image from me as a person. I agreed to open the store, and other MB&F Labs followed in Paris, Singapore and Taipei. In exchange, we had to increase a little our production.

How big is your company today and how is it structured?

Our team is currently of 63 employees including nine watchmakers and seven R&D engineers. Most watch brands have a ratio of 20 to 50 watchmakers for each R&D engineer. That difference reflects our unbridled creativity and the fact that we craft very small editions, as opposed to the large volumes produced by other firms. We also decided to bring much of the manufacturing in-house: 25% of our movement components and 80% of our watch cases are produced in house now. Our company crafted 396 timepieces in 2024. We usually have five to ten calibers (movements) at any given time, and one to two are launched every year. MB&F is a hotbed of creativity!

You currently live in Dubai. Why did you decide to move there, and how are you able to manage your company remotely?

I had given everything to MB&F. When my first daughter was born, I needed to spend much more time with my family. My father worked long hours to provide for his family and wasn’t able to spend time with me when I was little. So when I became a father, I knew I wanted to be more involved. It would’ve been impossible for me to maintain a healthy boundary with work whilst living in Geneva, near our workshops, so we decided to move.

We left for Dubai in 2014 with just three suitcases, since our idea was to try it out for a few months. And we’re still here today! Apart from the two weeks per month when I travel, I work from home, and stop when my two daughters come back from school. The move was actually also beneficial for the team since I was the king of micro-management! It was a pretty radical decision back then, when remote working did not exist. It is by far not the most efficient solution professionally but it is the only one I found to maintain a certain work/life balance.

Watchmaking was largely an artisanal practice when I first started. Since then, it’s gotten much more industrial, which has improved the reliability and reproducibility of timepieces, but the human aspect has often been left by the wayside. With MB&F, I’m desperately trying to bring it back.

Your timepieces stand out for their futuristic concepts inspired by pop culture. How would you describe the MB&F style?

Creativity connects me to my childhood. My first designs, the Horological Machines, were a kind of psychotherapy for me and recall the childhood heroes I mentioned earlier. But the link isn’t done consciously – I think up a design and then later realize it looks like a spaceship or a 1970’s car.

My other source of inspiration is the history of watchmaking itself. This is reflected in our Legacy Machines, which are round timepieces that reinvent traditional watchmaking in a much more intellectual process. They pay tribute to the great watchmakers of the 18th and 19th centuries who invented all the great “complications” that are still used today.

My approach isn’t always easy to explain. Many people have said they don’t understand what we’re trying to do. That is why we opened our first M.A.D. Gallery in Geneva in 2011. A gallery devoted to mechanical and kinetic art that helps amongst others explain our approach to watchmaking.

Earlier you mentioned your succession. Do you have a plan?

I started thinking about it when demand took off in 2020. I was only 55 years old, but I had started losing friends to illnesses. Founder succession is a major problem for Swiss small businesses but it is not a topic talked much about. My two daughters are still very young. I don’t know if they will want to take over the company one day, or if they’ll have the skills to do so.

In April 2022, I discussed my concerns with Chanel – an incredibly important family business that has always invested for the very long term. Two years later, Chanel acquired a 25% stake in MB&F. The agreement states amongst others that if none of my family members is in a position to take over the company when I pass away, Chanel will manage it.

You won the Aiguille d’Or – watchmaking’s most prestigious award – in 2022. Has that changed things for you?

We have won nine Grand Prix d'Horlogerie de Genève awards over the years, each in a different category. The crowning achievement was clearly the Aiguille d’Or that we received for our Legacy Machine Sequential EVO in 2022. This timepiece, designed by Stephen McDonnell, includes a chronograph that doesn’t lose amplitude when it’s started. That’s a major innovation, as all chronograph movements since they were first invented lose precision when they’re started or stopped; Stephen was the first person to find a solution to this problem. The awards haven’t had much of an effect on our sales, but they are a wonderful recognition of the incredible work done by our team.

Maximilian Büsser receives the 2022 Aiguille d’Or

Maximilian Büsser receives the 2022 Aiguille d’Or

Have you found this amazing entrepreneurial venture fulfilling?

Watchmaking was largely an artisanal practice when I first started. Since then, it’s gotten much more industrial, which has improved the reliability and reproducibility of timepieces, but the human aspect has often been left by the wayside. With MB&F, I’m desperately trying to bring it back. None of what we’ve accomplished was part of our initial plan, and our company has been much more successful than I could have dreamed. I have stayed true to my fundamentals: unbridled creativity, the joy of working with people who share the same values, and a desire to create beauty.

BIO

1991

Graduates from EPFL with a microengineering degree and begins his career with Jaeger-LeCoultre

1998

Appointed CEO of Harry Winston Rare Timepieces

2005

Founds MB&F in Geneva

2014

Moves with family to Dubai

2022

MB&F wins the Aiguille d’Or, the most prestigious award in watchmaking

Photos : MB&F

Comments0

Please log in to see or add a comment

Suggested Articles